Who says that drummers should only learn from drummers? Checking out the masters is very important, of course, but there’s a bunch of stuff we can learn from other instrumentalists. As the great Max Roach used to say, form in improvisation is crucial, as well as motivic development. The drumset doesn’t have a definite pitch, but still, we can give the idea of a melody by going from the lower sounds (bass drum) to the highest (hi hat) with everything in between. This opens up a whole new world, for we start thinking melodic.

Here are 3 lessons I learned from Brad Mehldau.

A BIT OF A BACKGROUND

What does Motivic Development mean?

As Josh Gottry in his Motivic Development Handout explains:

A motive is the smallest recognizable musical idea

– Repetition of motives is what lends coherence to a melody – A figure is not considered to be motivic unless it is repeated in some way.

– A motive can feature rhythmic elements and/or pitch or interval elements

– Any of the characteristic features of a motive can be varied in its repetitions (including pitch and rhythm).

Once we have a motive, we can generate melodic material by using several techniques:

- Repetition: the motive is played again at the same pitch level.

- Transposition: the motive is played again at a different pitch level. This can be:

- Exact: intervals retain the same quality and size

- Tonal (diatonic): intervals retain the same quality but not the same size. This varies according to the tonality.

- Sequence: transposition by the same distance several times in a row. This can be:

- Exact

- Tonal

- Modified

- Modulating

- Fragmentation: utilizing one portion of the motive to generate new melodic material.

- Augmentation: the motive is played with longer rhythmic values.

- Diminution: the motive is played with shorter rhythmic values.

- Inversion: the directions of the intervals (of the motive) are reversed.

- Retrograde: the motive is played backwards.

- Extension: Repetition of parts of the motive with small changes to make it longer.

By using these techniques, we can potentially create infinite material.

Now you would be asking: “yes, but why should we know this as drummers? Why is this important for us?”

The answer to this question is to hear in every solo of Max Roach, or Jeff Hamilton, or Ari Hoenig, just to mention a few. For all these masters, a drum solo is based on the transformation of a melodic fragment played on the drums and further developed. The (infinite) drum technique that they have serves them to work that way. It’s never the other way around. Personally, I believe this is the trademark that distinguishes the master from the professional.

And if we need to learn to play melodically, why don’t we learn directly from who always plays melodically? If you think about it, other instrumentalists play rhythmic patterns as well as we do, but with a pitch.

My approach to listening changed completely, as much as my drumming did. By experiencing music in this way – even more when playing live – we get a deeper contact with the other musicians, we synchronize on the same frequency, or maybe the same pitch 🙂

Transcribing solos from other instrumentalists forces us to face challenges on our instrument that wouldn’t show up otherwise. The mechanic behind a saxophone solo is completely different from ours. The time feeling is different from what we’re used to. Usually, we can’t drag or lay back or push. A piano player could. We play our instrument with four limbs and that means orchestrating, for we have several timbres available. The trumpet doesn’t.

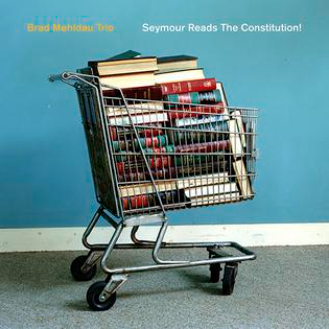

I analyzed one of my favorite tunes of my hero Brad Mehldau with Larry Grenadier and Jeff Ballard: Seymour reads the constitution.

The self-titled album was released in 2018 by Nonesuch Records. If you didn’t do it yet, go check it out!! (Click on the image for Spotify link)

In this video I transcribed Brad’s solo from min. 2:57 to 3:57 and orchestrated it on 4 drum pads. As the solo goes on, you’ll be able to see the various techniques described at the beginning of this article.

3 THINGS I LEARNED

1. START SMALL

You don’t need to show off everything you have. A lot of notes can impress a beginner and that only for a short time. If not contextualized, people will have quickly enough. Brad starts with 3 notes. He elaborates them and plays with all the elements he has available. The listener wants more and eventually, he gives them more.

2. KEEP THE FORM IN MIND

How does a dialogue go? You begin with one sentence, usually short. Then comes the answer. From that answer comes a new question. You add more details and get more specific, as your sentences get longer. Again, an answer comes. And so on and so forth.

When you use this in music, you become understandable even if you play complicated harmonies or melodies.

3. DON’T BE AFRAID OF RESTS!

Music is not the notes, but the silence in between.

So stated Mozart. I would trust him.

We always feel the need to fill every single space given with mindless notes. Often, we even force that space. If you think about it, how tough is that? Once more the example of a dialogue: what would you think of someone who keeps talking and not listening to what you say? You didn’t even finish your question and the other person starts talking about something completely different.

Check out the music sheet and count the rests Brad plays. This has a key role in the building up of the solo.

Take the time and give music the time. More contextualized and pertinent ideas will generate from this.

CONCLUSIONS

Thanks for reading this article, I hope it can inspire you to think out of the box and shift your approach. I’ll come back with more articles about improvisation, but for now…let’s enjoy this one!