As you see, there are tons of different uses you could make, but all of them points out to the same direction: clarity.

By writing down what is going on in your head, you verbalize it and give it shape. The thoughts are then clear and visible, and the cloud of (destructive) feelings that thoughts bring with them finally vanishes.

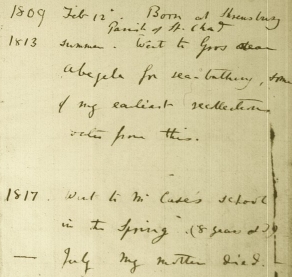

As reported from The Daily Stoic, Eugène Delacroix described this really explicitly:

“My mind is continually occupied in useless scheming…They burn me up and lay my mind to waste. The enemy is within my gates.”

And again:

“I am taking up my Journal again after a long break. I think it may be a way of calming this nervous excitement that has been worrying me for so long.”

Most of the people are intimidated by keeping a journal for several reasons. Some think that it shows weakness, in the context of a society that wants you always strong and with no flaws. The truth has never been so far from reality. Everyone, even the coolest or toughest person on earth has his or her moments of weakness, trouble, fear and uncertainty. Simply because it’s part of being human.

The biggest benefit you would gain by starting journaling would be becoming aware of what your hidden side looks like. It might look like opening Pandora’s box, that’s true. But truth is, that Pandora’s box is open anyway, and each one of us finds his or her way to cope with it. It could be sporting, using drugs, or alcohol. It could be being violent and aggressive. It could be looking for distractions to keep your mind busy.

Or it could be facing the problem by analyzing it as closely as possible.

As I said before, by writing down thoughts and emotions they become tangible. This process can be painful in some cases, but the good news is that it gets better as time goes by. Why? Because you experience that 99% of what has been torturing you actually…doesn’t exist. Or that the fears or feelings you feared can be broken down in a way that makes them easier to be assimilated.

John Dewey explains it way better than me:

“We don’t learn from experience, we learn from reflecting on experience”

By constantly recording the recurring thoughts you have, your mind makes a clear distinction between what is real and what is just projection, anticipation.

Some people are intimidated because keeping a journal might look like a heavy task to carry on. So far, we know that there are several reasons to keep a journal. Furthermore, there are several techniques and tips to do it.